Former lakeshore pastor, best-selling author explore Christian nationalism in new projects

Two West Michigan authors have produced separate projects that explore the intersection of faith and politics in today’s cultural and political climate.

OTTAWA COUNTY — Christian nationalism is “having a moment,” with a particularly polarizing election year, according to experts and academics. Now, two West Michigan authors have produced separate projects that explore the intersection of faith and politics in today’s cultural and political climate.

Loosely defined, Christian nationalism is the development of politics and culture that reflect America as a Christian nation.

“It’s the idea that the United States was founded as a Christian nation and should be defended as such,” said Kristin Kobes Du Mez, an American historian, author and professor of history and gender studies at Calvin University. “It’s a modern manifestation of this mythical idea that God has a special plan for America — if it responds obediently.”

‘For Our Daughters’

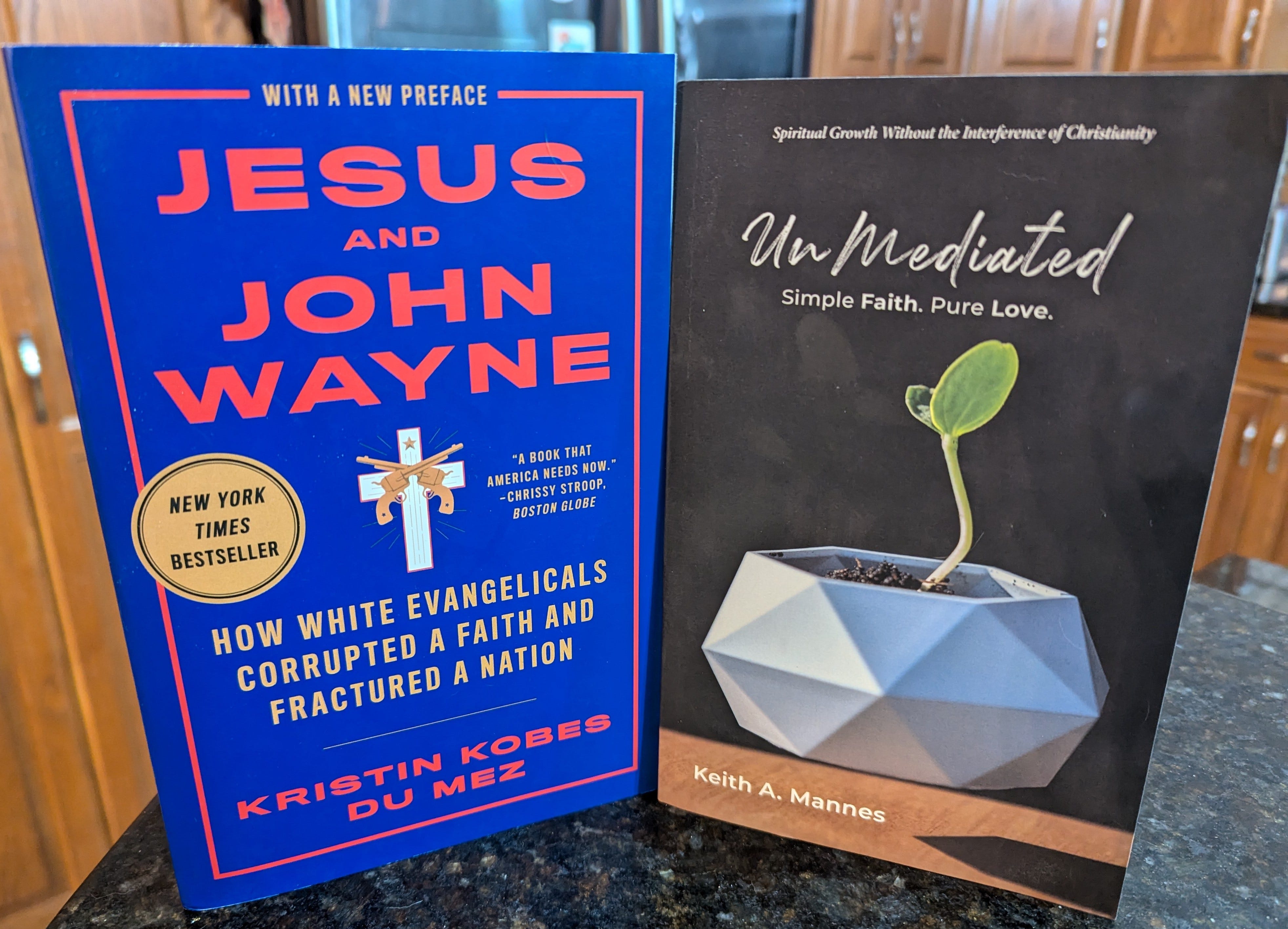

Du Mez is the author of “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation,” the critically acclaimed book that examines the white evangelical affinity for former President Donald J. Trump.

The book, released in 2020, made The New York Times bestsellers list. Now, Du Mez has produced a film borne out of interviews for her book.

“Just months after ‘Jesus and John Wayne’ released, three conservative evangelical women asked to speak with me,” Du Mez said. “To my surprise, they thanked me and asked how they could help. ‘It’s too late for us,’ they told me. ‘We’ve made our choices, and we can’t walk away from the lives we’ve made. But we want something different for our daughters.’ I’ve carried their words with me. This film is for them, and for their daughters.”

“For Our Daughters” delves into what Du Mez describes as “the brave sexual and spiritual abuse survivors within the church who have shared their stories, and those who have not yet spoken.”

The film features several survivors, including Rachael Denhollander, who famously was the first woman to publicly accuse former Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar of sexual assault. Nassar was later sentenced to more than 100 years in prison for sexually assaulting hundreds young women and girls as part of the largest sexual abuse scandal in sports history.

Du Mez said the genesis of the project began when Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Carl Byker, who ultimately directed the project, pitched the idea of a documentary.

“As we were kind of thinking about which direction to take a feature documentary or a limited series, we just started initial interviews, and we actually started with the women's voices and the last chapter of ‘Jesus and John Wayne,’ which features kind of the darker side of this militant Christian patriarchy, or inside Evangelical churches, and so we started doing a couple of interviews, and I think we were both kind of blown away at the power of these women's stories,” Du Mez said.

“I was familiar with the stories, but it was still something entirely different to hear them firsthand and in their entirety, because so much of this issue has been kind of debated in the media or on social media in little snippets, and their detractors have done so much to try to discredit them and to attack them and to smear their reputations,” she said. “It is just stunning to hear what has been going on inside some of these churches and denominations, and also to see how courageous these women are, and to hear the clarity with which they can describe, now in hindsight, what happened to them.”

One survivor describes in the film how difficult it was to come forward about her abuse, only to see the church she attended to rally around him.

“She watched her predator go on and continue his abusive patterns, even after she had reported him to the pastors with authority over him,” Du Mez said.

The survivor eventually came forward again years later publicly after two young victims made allegations of abuse against the same man.

“Only after she came across another case of two little girls and she reached out and was told ‘these girls are too young to testify. They can't withstand what's going to be coming at them.’ And she said: ‘Okay, let me do it,’” Du Mez said. “So part of the purpose of this film is to let women know, let survivors know and let members of church communities know: These are the dynamics, these are the patterns happening over and over again.”

Du Mez said the film also draws the correlation between sexual abuse in evangelical churches with the current U.S. political climate — directly noting that Trump, who is running for president after losing re-election in 2020, has had numerous sexual assault allegations made against him since the 1970s.

“There’s a political context here, and we don't shy away from that in the film,” she said, “and we understand that political choices are complex, but we want Christian women and all Americans, frankly, to add these stories into that mix, in terms of understanding power dynamics, understanding what goes along with this Christian nationalist agenda that supports patriarchal gender roles, that defines women's freedom not according to kind of the rights guaranteed in the Constitution, but according to their understanding of what God wants for them.”

As the country is set to decide if Trump should be sent back to the Oval Office — he’s running against Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris — Du Mez said the urgency of the political moment is critical in how the country will move forward.

“Given what was going on in our country and given this urgent political moment, we wanted to put these voices out there and give them the widest hearing possible, both inside Christian spaces and because the film does draw a direct line to this larger Christian nationalist movement that really is on the ballot this November.

“We thought all Americans need to hear their story,” Du Mez said.

Even though the film acknowledges a connection to politics, Du Mez argued that the film isn’t political.

“I'm essentially riffing off of language in Project 2025 … there's a striking sentence there that says, essentially, the Constitution guarantees Americans the right to do what they ought to do, not what they want to do. And I think that's very telling, and that rings alarm bells for any of us who are familiar with these Christian nationalist networks and how they apply that to women and to children,” Du Mez said.

“That's the broader purpose for this film, and I don't think that we're politicizing the topic. I actually came upon this topic of abuse in Christian spaces when I was researching the intersection of evangelical gender ideals and politics in the case of this militant Christian masculinity as intertwined with Christian nationalism, that led me to their stories. And so it was kind of an inorganic research project, and now we're just presenting those stories in the context of that larger political context.”

Read More: Christian nationalism is gripping the nation — has it arrived in Ottawa County?

Du Mez, said there is an ingrained “deflection” inside Christian organizations and networks that she called “astonishing.”

“When you encounter abuse, then you think the people with power are going to do what's right, but the frequency with which that does not happen really is stunning,” she said. “And so it's not just the problem of predators. … What we're looking at in evangelical churches is also widespread complicity among church members, among church leaders, when these cases surface.”

That deflection includes often “blaming the victim” for “seducing” the offender, Du Mez said.

“At first, I couldn't believe the frequency with which victims got blamed, even if they were young girls, for seducing their abuser, for tempting them. Wives were blamed if their husbands were abusing even their own child because they were not fulfilling their husband's sexual needs. And then the kind of knee-jerk reaction among church members to circle the wagons and protect the predator, if he is the pastor, a man of God, and to shun the victim. More often than not, in the stories that I hear, it's the woman, the victim, who is pushed out of the church. And the man will just quietly move on and do it all over again in another church, because we don't want to air our dirty laundry,” she said.

Du Mez points to deeper evangelical teachings of submission and authority.

“It situates so many women in these spaces as unable even to identify what is happening to them as abuse, because it has been drilled into them: obedience to authority, obedience to the man in authority over you. He represents God. He is a man of God. And so a lot of these women really, especially as girls growing up in this space, they don't have the language to even recognize what is happening, or a sense that they would have any agency in these situations,” she said.

“But then also, theologically, there are conservative evangelical teachings on sex, and this is that men have a kind of irrepressible sexual drive because God filled them with testosterone, but that's the way that God designed them to be — aggressive, and to channel that aggression and that power into leadership. That's God's plan,” she said.

“And Rachael (Denhollander) articulates this idea of sexuality very well in the film … that it's women's job to serve men and to meet their sexual needs. And that's kind of how that morality works. Boys will be boys. Women have to guard their purity against these men and boys and not tempt them, then submit whenever they want anyway, and if it goes wrong — it's your fault.”

“It's women's job to serve men and to meet their sexual needs. And that's kind

of how that morality works. Boys will be boys. Women have to guard their purity against

these men and boys and not tempt them, then submit whenever they want anyway, and

if it goes wrong — it's your fault.” ~ Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Du Mez intentionally published the film on YouTube in order to make it free and accessible to all.

“We made the deliberate choice not to put it on a streaming platform, but to put it up on YouTube because this is a not for-profit venture, and we wanted to be sure any woman who could be helped by this film had access to it without any barriers,” she said.

She hopes that the film brings awareness to those who aren’t familiar with the topic and hope to victims and their family members.

“I have such faith in the power of these women's stories. I just want people to take it in and sit with it, and then I trust that there's going to be some follow up from a lot of viewers, because, and I've already heard from so many, saying: ‘This is my story, too,’ and it is so helpful to have this to now show to other people who couldn't see them,” Du Mez said.

Watch the film at youtube.com/watch?v=IkES4X_qb6c. To learn more about the film and to connect with resources, visit forourdaughtersfilm.com.

‘UnMediated: Simple Faith. Pure Love’

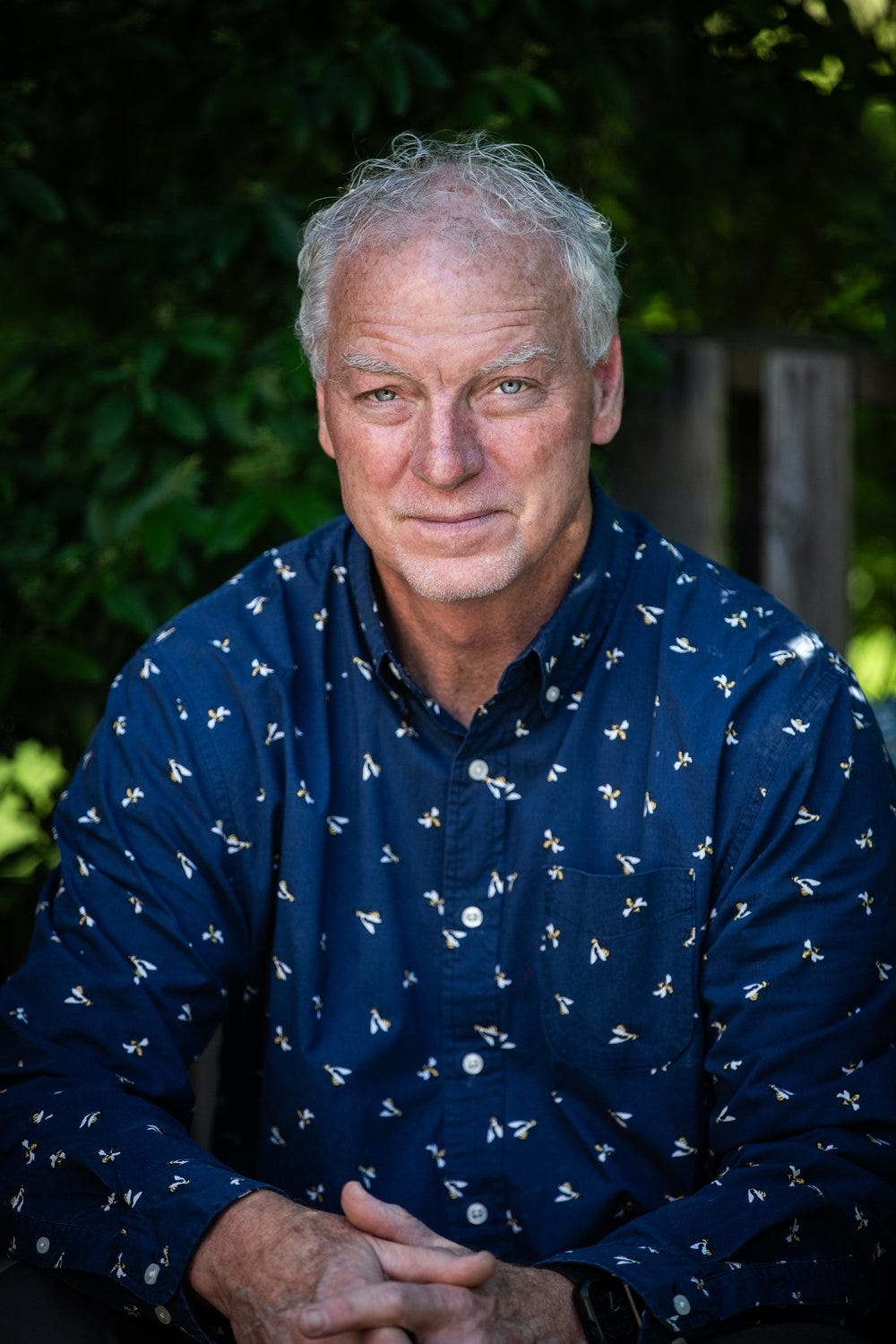

Keith Mannes knows evangelical spaces well.

After serving as a pastor in West Michigan for over 30 years, he quit in October 2020 after he said “toxic” politics infiltrated religion leading to the church “abandoning its role” as the conscience of the state in support of then-President Trump.

Mannes has written about the experience in his new book, “UnMediated: Simple Faith. Pure Love.”

“The instigation of this project, in my own heart, is the awareness that I felt, and that many people feel, that the church, simply put, has largely lost the message and intent of Jesus. And because of its intense adulation of Donald Trump and the principles and attitudes of Trumpism, I could not and now I find increasing numbers of people just cannot be a part of that, so I decided that in this moment, I may only have a little voice, but what voice I have, I want to use, and whether only a few people read this or many, I want to try to convey the danger of religious Trumpism and to portray its offense in the church as we know it, in this conservative region of West Michigan,” Mannes said.

The evangelical reaction to Trump’s victory in 2016 showed that the Christian right’s religious identity is becoming more infused with politics, particularly the politics of the Republican Party. Mannes said Trump’s rise to political prominence saw many evangelicals believing that the former president is “an instrument of God,” referring to some of the stories found in the Old Testament.

“They believe in an Old Testament kind of God,” Mannes said, “and believe that by violence and bloodshed, if necessary, it is they who are called and chosen to rule the world, and certainly to rule this nation, in their particular way of thinking about God, life and faith.”

Part of the problem, Mannes said, is that non-hardcore evangelicals don’t challenge problematic rhetoric and behavior.

“Around them is a much larger percentage of really good and beautiful people who go to church and just want to have faith, but appease that view, or to some degree feel that that has validity for them,” Mannes said. “They agree enough to not stand in its way and to appease it. The greater population around it are the main reason Donald Trump ever made it to the presidency and still view him as not just a means to an end — I think there might be some truth to that — but really believe that he fits the bill of what needs to happen in the world right now, from the hand of God.”

Mannes said he, like Du Mez, was raised in the Christian faith and that he appreciates those early experiences — but that there were red flags.

“We talked about Jesus as the essence of everything, but we thought of ourselves and identified ourselves as Old Testament Israelites … like our way of living and structuring moral things and our lives had to do with all of the Old Testament,” he said. “That's where we spent a lot of our time, is in the Old Testament stories which are very polygamous and which are very violent. And then at the end, we would talk about Jesus for salvation.”

The problem, Mannes said, is that evangelical Christianity teaches followers that they are the chosen people of God, which leads to dangerous levels of entitlement.

“It is my opinion that when you're soaked in that way of thinking and in that idea of chosenness — that we are chosen to cast out the wicked and to purify the land and, at times, violence and bloodshed are necessary — when you marinate in that for your life, you can be a very gentle and kind person in the world, but deep in your heart when there's a problem and you want to straighten it out, you know that sometimes you believe then that sometimes violence is necessary.”

Mannes said that partially explains why the evangelical community largely supports Trump for president, despite his multiple marriages and sexual indiscretions.

“I think that's why there's a lot of permissiveness in the Christian community, to that violent language and to those sexual indiscretions,” Mannes said.

As a former evangelical pastor, Mannes said Trump taps into a “red-hot writing core” of God-driven dominance found in many conservative Christian teachings.

“When you ask how this can happen, I look at people from my former faith tradition. They go to really nice churches and the preachers try to teach good and biblical and doctrinal things, but they're going home and they're listening to preachers on TV from that red-hot writhing religious core, and don't really realize it, but that’s where they're getting a lot of their fuel,” Mannes said, referring to conservative media channels like FOX News and the One America News Network. “I think that there are good and decent preachers from those churches who don't even realize that they're sort of being out-fueled from that other realm of religious teaching.”

Mannes said the surge of Christian nationalism over the past decade can be attributed, in part, to the religious right feeling “weakened” as church membership continues to decline across most major religions.

A 2024 Pew Research Center survey found that 80% of U.S. adults said religion’s role in American life is shrinking.

“I think, for a long time, people in my former religious space felt weakened and they felt that marginalization, and took that as persecution, or as a sign that they had the truth, and everybody else was turning from the truth,” Mannes said. “And then when Donald Trump stood up and said, ‘Christianity will have power again,’ there was just a whooshing sound of reaction to that.”

And in that reaction, Mannes said it became nearly impossible for local faith leaders to criticize Trump or to disagree with what he was telling supporters, another topic explored in the book.

“I describe the experiences that I saw that led me to conclude that the church had been really quite captivated by Trumpism, and that there was no way even to speak about it or teach about it, or even refer to it without a pastor losing her or his job,” Mannes said. “There just was no way to confront it. And so I left my church and I divorced my denomination in order to speak freely about convictions of my heart.”

Mannes said the experience led him to lose his faith completely.

“I go on to describe how I lost my faith and what that actually felt like to go through that time of just being dead and numb,” he said.

“My hope is to give some oxygen to people who are in churches and they can sense that something is deeply wrong. Many people tell me: ‘You just put words to what I was feeling but didn't know how to say.’ I hope it gives some courage to people who have left their churches and don't know what to do … where you're like ‘what's happening to me’ and you can't really describe it. So I tried to say to them: ‘Hey, your soul is working just fine. You just listen to the heartbeat of God in your own soul, and you'll be just fine.’” ~ Keith Mannes

Mannes still wanted to help people, however, becoming an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ and working as a chaplain with local hospice organizations.

“I describe small moments where, in my hospice, I work with dying patients. When I experience little touches, I think of our divine experience,” he said.

Mannes said he hopes that by writing the book, he can validate other Christians and former Christians who have gone through similar experiences.

“My hope is to give some oxygen to people who are in churches and they can sense that something is deeply wrong,” Mannes said. “Many people tell me: ‘You just put words to what I was feeling but didn't know how to say.’ I hope it gives some courage to people who have left their churches and don't know what to do … where you're like ‘what's happening to me’ and you can't really describe it. So I tried to say to them: ‘Hey, your soul is working just fine. You just listen to the heartbeat of God in your own soul, and you'll be just fine.’”

Mannes also holds out hope that he reaches some people still entrenched in those evangelical spaces.

“I wrote this book with urgency, and I feel that sense of urgency to say: Maybe somebody from my religious background will actually read this and say, ‘Wow, is that what it feels like to be around us?’” he said.

Sentinel Leach is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“But more than that, it’s for people who have sensed that something is deeply wrong to be courageous right now, and to be able to speak and act, to be able to say, ‘I don't have to think like this or believe or act like this, and certainly will not vote like the people of my former faith tradition tell me I should.’”

Mannes said it’s alright for people to not have all the answers they seek, but to be brave enough to listen to their intuition when they know things aren’t right for them — in faith, politics and life.

“You don't have to have everything figured out,” he said. “But if you know where Jesus is not, get out of there. Get out and go anywhere else and you'll figure it out.

“UnMediated” can be found at Mannes’ website, keithamannes.com, and on Amazon and Kindle.

— Contact Sarah Leach at SentinelLeach@gmail.com. Follow her on Twitter @SentinelLeach. Subscribe to her content at sentinelleach.substack.com.