Judge signals that officials' private devices exempt from FOIA requests

An Allegan County judge signaled Monday that she likely would rule that Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act does not cover public officials’ private devices and accounts.

ALLEGAN — An Allegan County judge signaled Monday that she likely would rule that Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act does not cover public officials’ private devices and accounts.

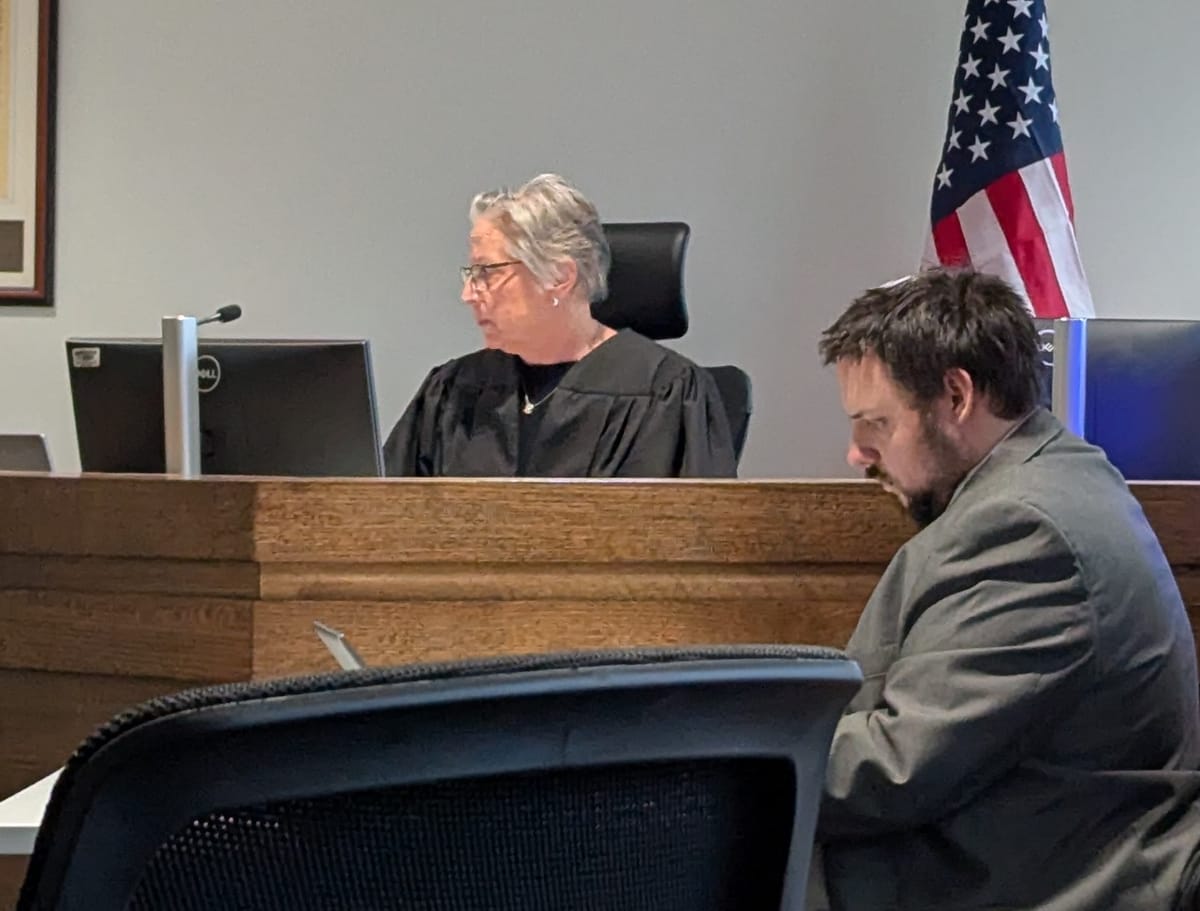

The impending decision by 48th Circuit Court Judge Margaret Bakker, who said a written opinion will be issued no later than Feb. 17, comes after Bakker heard arguments in the lawsuit Hill and Sanner v. Ottawa County.

The two plaintiffs, Adrea Hill and Luke Sanner, filed the joint lawsuit in October 2024 after the county denied their separate requests to see communications of public officials who are members of far-right fundamentalist group Ottawa Impact, which held a majority on the board of commissioners in 2023 and 2024.

Both the county and the Ottawa County Board of Commissioners are named in the lawsuit.

Read More: Sixth lawsuit filed against Ottawa County Board of Commissioners under Ottawa Impact leadership

Hill asked for emails and text messages during a five-hour window on one day in 2024 by one OI-aligned public official on the county’s compensation commission. Sanner asked for digital communications between six OI-aligned county commissioners from a two-day window in 2023.

Despite the fairly specific requests, Bakker framed both requests as “broad” and “breathtaking in scope.”

“Much like the rest of the legal world, the advancement of technology presents significant problems for the judicial world,” Bakker said Monday. “I think that there's a significant public policy issue that hasn't been addressed by the courts. I would be very surprised if whatever I do doesn't get reviewed by the court of appeals, which is fine. They obviously have more resources than I do for this particular situation.”

Although a formal decision wasn’t announced after Monday’s hearing, Bakker indicated that she likely will rule in favor of the county, which denied Hill’s and Sanner’s requests for the records.

“Is it fair to submit a FOIA that is fairly wide and does it make sense to invade someone’s private messages?” Bakker asked.

The Hill FOIA request

In May 2024, Hill filed a request for "text messages and emails related to county business sent or received by Lynn Janson on Thursday, May 23, from noon until 5 p.m."

The request came after the county’s Officers’ Compensation Commission, comprised of citizens appointed by the board of commissioners, voted 3-1 on April 11 to give raises to county commissioners beginning in 2025.

The raises were controversial because the compensation commission, of which Janson is a member, staged a “re-enactment” of an April meeting on May 23 after the earlier meeting was not properly noticed in compliance with Michigan’s Open Meetings Act.

At the re-enactment, the compensation commission voted 5-0 to re-approve two measures that would give raises to countywide elected offices and road commissioners, however, the action occurred outside of the compensation commission’s 45-day window to make recommendations to the county commission for raises.

The validity of whether or not the redo was legal, however, is in doubt. In emails Jackson sent to Anderson and the commission members, he said Thursday’s meeting was outside of the commission’s 45-day window to operate.

The May 23 meeting stalled for nearly 20 minutes and Janson announced that the county’s corporation counsel was on its way to the meeting room at the Fillmore Complex, despite Janson not leaving the room, nor taking any calls prior to the statement.

Hill’s request seemingly is predicated on the possibility that Janson could have texted county staff, including corporation counsel, in order to make his statement make sense.

Attorney Sarah Riley-Howard, who is representing Hill and Sanner, said county corporation counsel Jack Jordan responded to Hill's request with an estimated fee of $352.79 and claimed the request “would require a search of communications on the county server of all of its more than 1,000 employees.”

Hill protested the estimated fee, saying all that was required was searching communications related to county business sent or received by Janson.

In a July 9 response to Hill’s appeal, Jordan denied that the fees were inflated, but did not address Hill’s claim that Jordan “proposed an inflated and unnecessary search of all county employees to fulfill her FOIA request,” according to the complaint.

In a follow-up communication, corporation counsel refused to produce the records to Hill claiming it was outside of the county’s purview, as Janson isn’t an employee.

The county “did not address the fact that Lynn Janson is a member of the Ottawa County Compensation Commission, and as such, is a public official in that capacity and that his communications are subject to disclosure under FOIA,” Howard said.

The compensation commission was formed in late 2005 and makes determinations for the compensation of county elected officials in even-numbered years.

State statute requires that compensation commissions must comply with Michigan’s Open Meetings Act. According to Michigan’s FOIA law, all “public records” are subject to possible disclosure unless specifically exempted by statute.

A “public record” is a writing that is prepared, owned, used, in the possession of, or retained by a public body in the performance of an official function, from the time it is created. Under this broad definition, emails, text messages, social media posts, and even voicemails could be subject to disclosure under FOIA if made in the furtherance of government business, according to case law cited by the Michigan Association of Counties.

“Specifically, Defendants have refused to require public officials to search all communication accounts and on all devices — public-owned and personally owned — for communications concerning matters of public business for lawfully required disclosure in response to Plaintiffs' FOIA request,” Howard said in the original lawsuit, asserting that the county’s position is not supported by Michigan law.

The Sanner FOIA request

Sanner filed a FOIA request on Nov. 5, 2023, asking for instant messaging communications between Ottawa Impact-aligned Ottawa County commissioners on Oct. 24 and Oct. 25 — dates that coincided with a failed termination hearing for the county’s administrative health officer.

Ottawa Impact is a far-right fundamentalist group created in 2021 by then-board Chair Joe Moss after he took issue with pre-K-6 school mask mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic. The group currently controls six seats on the 11-member board of commissioners.

In his request, asked for “communications found on personal devices used for county-related business as well as county owned devices."

On Nov. 29, the county denied Sanner's request claiming personal devices weren’t under the county’s purview.

“Defendants took the position that such communications were not within the definition of ‘public record’ under FOIA,” Howard said.

On Dec. 6, Sanner appealed the denial of the records, however, he claims that the county never responded within 10 business days — which is what is required for the appeals process under Michigan law.

When Sanner didn’t receive a response, he followed up by email to the county on Feb. 14, and on May 2 asking about the status of his appeal.

May 3, the county responded to Sanner denying his appeal, claiming they responded to his appeal in a timely manner on Dec. 21, but erroneously sent the response to an incorrect email address.

Howard said both examples show that the county isn’t following appropriate processes and procedures to ensure public record access exists for residents.

Hill and Sanner are seeking:

- A declaration that Ottawa County violated Michigan’s FOIA law.

- A court-ordered injunction requiring the county to produce the requested documents for Hill’s and Sanner’s respective requests within 14 days.

- Reasonable attorney's fees.

- A complete accounting under oath by a corporate witness as to whether any responsive documents have potentially and/or likely been destroyed.

What’s happening now

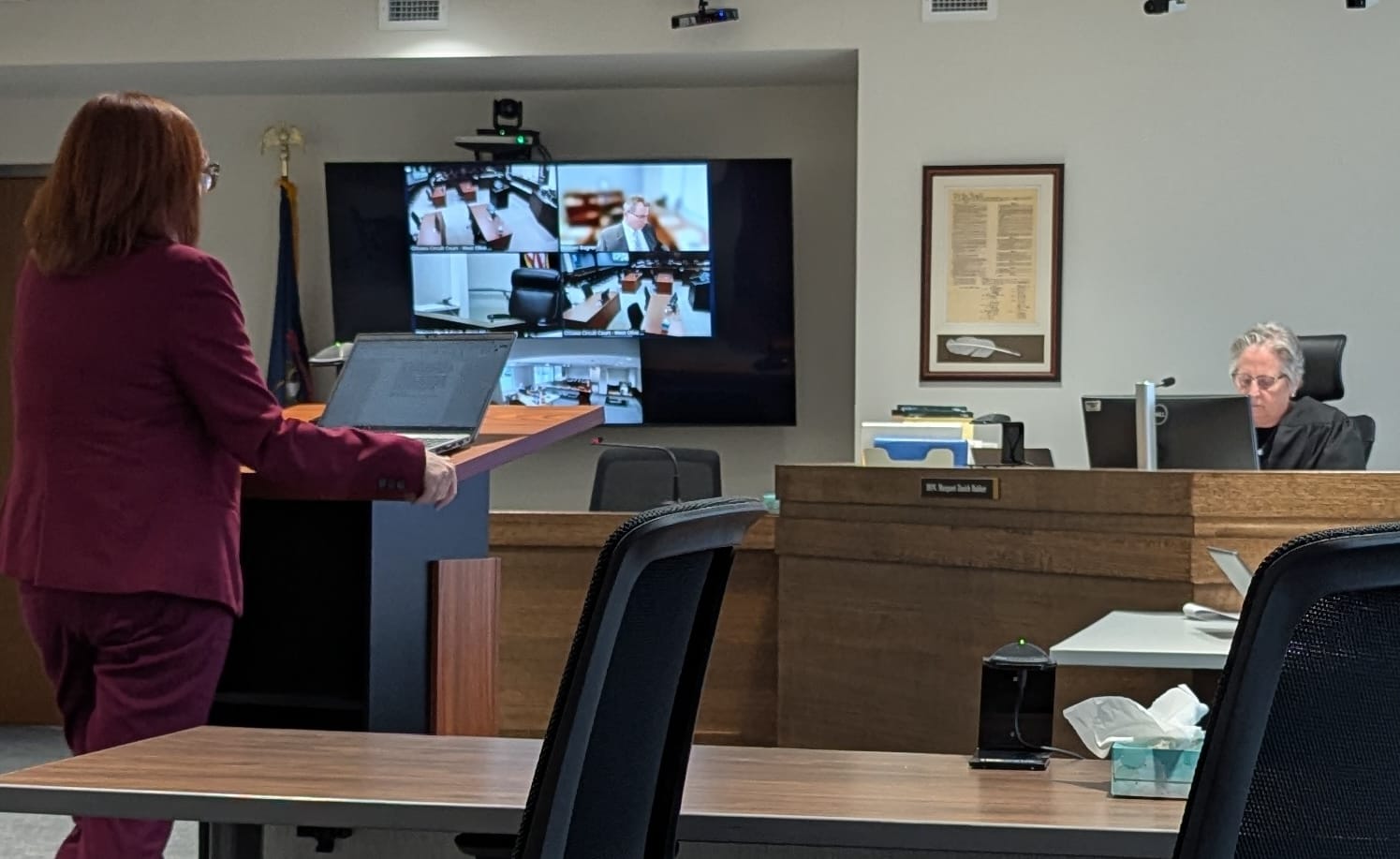

In her arguments, Howard told Bakker that FOIA does not mandate that requesters prove that records exist prior to making requests and that private devices as well as private messages would never be seen by a requester.

“A public officer like the compensation commission member or county commissioner would not have to turn over their phone to me or a FOIA requester,” Howard said Monday. “What should happen here is just like any other FOIA request, someone on behalf of the entity, whether it's the FOIA officer, county administrator, or the lawyer has to review what there is, and then they make a determination if, under the statutory language of FOIA, it needs to be produced … and turned over.”

“It might be that they send a hundred texts, none of which have anything to do with the public decision, and then the public body makes that call and produces or they don't,” Howard said. “There's nothing about this case that would require either Mr. Janson or any of those commissioners to hand over their entire device. Just someone on behalf of the county needs to review those and determine if they must be produced.”

County litigation attorney Mike Bogren, who appeared virtually at the hearing via Zoom, admitted that the county has not taken steps to gauge what, if any, records exist that would be applicable to the plaintiffs’ separate requests.

He also said if the county’s FOIA officer, Lanae Monera, had asked Janson for his phone and Janson refused, there would be no way to fulfill the FOIA request.

If that request had been made, and Ms. Monera had said to Mr. Janson, I need to see your iPhone and look at your text messages, and he says, ‘No,’ I mean, where does that leave us? Because there's no enforcement mechanism to force an individual to turn over their personal device,” Bogren said.

Howard said communications between public officials that touch on public business or affect public decision-making should be subject to public disclosure, regardless of the medium in which they’re communicated.

“A communication between two people is no different than if two commissioners had a discussion in the middle of a public meeting that's open to the public and known to the public in the same way communicating via text message or instant message during a meeting, which is the crux of the standard request, assuming that they're talking about public business or a public issue before the commission,” Howard said. “If they're talking about where they want to go out for dinner after the meeting, that's not a matter of public right.”

She also contended that if public officials don’t comply with the bodies to which they belong, the onus to comply lies with the public body — and that the FOIA requester shouldn’t be penalized.

“You have to ask each of these people if there's anything on the devices. If they say ‘no,’ there's nothing I can do to prove that that's not true, and if Mr. Bogren has no reason to believe that that’s not a true statement, that's the end of the matter,” Howard said. “However, there should be some serious consequences if it returns up, if that's untrue, that's between Mr. Bogren and his client (the county).”

Bogren said if the court were to grant Hill’s and Sanner’s requests, it would send a chilling effect on people considering running for office.

“(If we can) review everything on their phone to determine whether something is part of the performance of an official function, nobody's going to want to be a public official,” he said. “That's a judgment for the legislature, and it should be with debate, when they can take into account these competing interests.”

Howard argued the inverse, saying if the court didn’t grant her clients’ requests, public officials will start using private devices to subvert public transparency tools.

“Public officials could very easily subvert the entire purpose of FOIA,” she said. “If you know that your personal communication accounts and devices aren't subject to FOIA, you could conduct all communication related to public business that you wanted to shield from the public on those personal devices.”

Bakker said she was “concerned that there's not sufficient showing that these things are part of a public record” and likened the two requests to “a fishing expedition.”

Michigan FOIA law does not require a requester to “show cause” — a legal term that pertains to justifying something they want.

“There's a variety of aspects. My initial response is that there's been questions so broad and contentable and impossible to really resolve … but also I think it is an invasion of privacy to have that broad ability to view [records when] there was absolutely no indication that [they] became a public record,” Bakker said.

Howard’s law firm, Grand-Rapids-based Pinsky Smith, posted on its Facebook page on Monday that if Bakker rules in favor of the county, the decision will be appealed.

“Sarah was honored to argue for plaintiffs in a FOIA case against Ottawa County today. Allegan County Judge Bakker indicated that she was likely to hold that FOIA does not cover public officials’ private devices and accounts, and as a result, she will likely hold for the County. So we are prepared to appeal this important issue to the Court of Appeals - stay tuned,” the law firm said in the post.

Hill and Sanner, who were both present at the hearing, declined to comment Monday.

Judge connected to controversial FOIA

Bakker herself made headlines after a FOIA filed in 2020 revealed inappropriate communications during a criminal trial.

Criminal defense attorney Mike Villar, who was challenging then-incumbent Myrene Koch for the Allegan County prosecutor position, filed a FOIA request that showed Bakker had ex parte (one-sided) communications with Koch while Bakker was overseeing a criminal trial Koch’s office was prosecuting.

In the emails, Bakker asked Koch for additional evidence about the case that was not presented to the jury or defense attorney and went on to criticize the investigation skills of the Michigan State Police.

Ex parte communication is not allowed because all parties in a legal matter, including the judge, the prosecuting attorney and the defense attorney should have access to the same information and evidence for a proceeding to be considered fair.

Once the emails were released publicly, the defendant’s attorney appealed the conviction and asked the higher courts to order a new trial for his client.

In September 2024, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled it was unethical for Bakker and Koch to have off-the-record discussions during the trial, but the misconduct was not enough to reverse the conviction and re-try the case, according to Michigan Public Radio.

The Supreme Court majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice Elizabeth Clement, did appear to hold open the possibility of sanctions for Bakker.

“The trial judge’s actions fell short of the high ethical standards that Michigan jurists are expected to uphold, and regrettably, her behavior has the potential to erode public confidence in the integrity of our justice system,” she wrote. “Still, the issue before us is not whether the trial judge should be sanctioned for her misconduct.”

Villar, who has since been elected as the Allegan County prosecutor in 2024, filed charges with the Michigan Judicial Tenure Commission when he released the emails in 2020. As of this writing, the JTC has not indicated that it has sanctioned Bakker.

— Sarah Leach is the executive editor of the Ottawa News Network. Contact her at sleach@ottawanewsnetwork.org. Follow her on Twitter @ONNLeach.