Ottawa County approves $563K contract to restore Crockery Lake as process faces criticism

Questions remain on why the deal happened with little public discussion and didn’t follow the county’s traditional purchasing policies.

OTTAWA COUNTY — The recent decision by the Ottawa County Board of Commissioners to give more than $560,000 to Chester Township to “revitalize” Crockery Lake was seemingly a sudden and contentious decision with little public process.

The plan, however, was in development for many months, with only select officials involved in the process, and questions remain on why the deal happened with little public discussion and didn’t follow the county’s traditional purchasing policies.

Now the plan approved Dec. 10 is in doubt as at least one legal challenge was filed this week, claiming the board exceeded its legal authority in paying the township the entire amount — despite being a five-year remediation plan — so that the current Ottawa Impact majority on the board could complete the deal before losing power.

Read More: Howard challenges legality of severance agreements, Crockery Lake contract

How it started

Crockery Lake is an inland lake that occupies about 106 square acres in the northeast corner of Ottawa County, in what some residents refer to as the county’s “chimney.”

Originally populated with indigenous Native Americans, much of the area that is now Ottawa County consisted of wetlands, which served as natural filters of the local waterways, said Al Steinman, a professor and former longtime director at Grand Valley State University’s Annis Water Resources Institute.

“Europeans came in and drained all these wetlands and many are usually just upstream of all of our river mouth lakes,” Steinman said.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, much of the wetlands were drained and turned into crop fields, such as celery, which Steinman called a “quite common phenomenon here in West Michigan.”

“They farmed that until about the 1980s when it no longer was economically viable,” he said. “And then they turned off the pumps, and these fields basically filled up with water.”

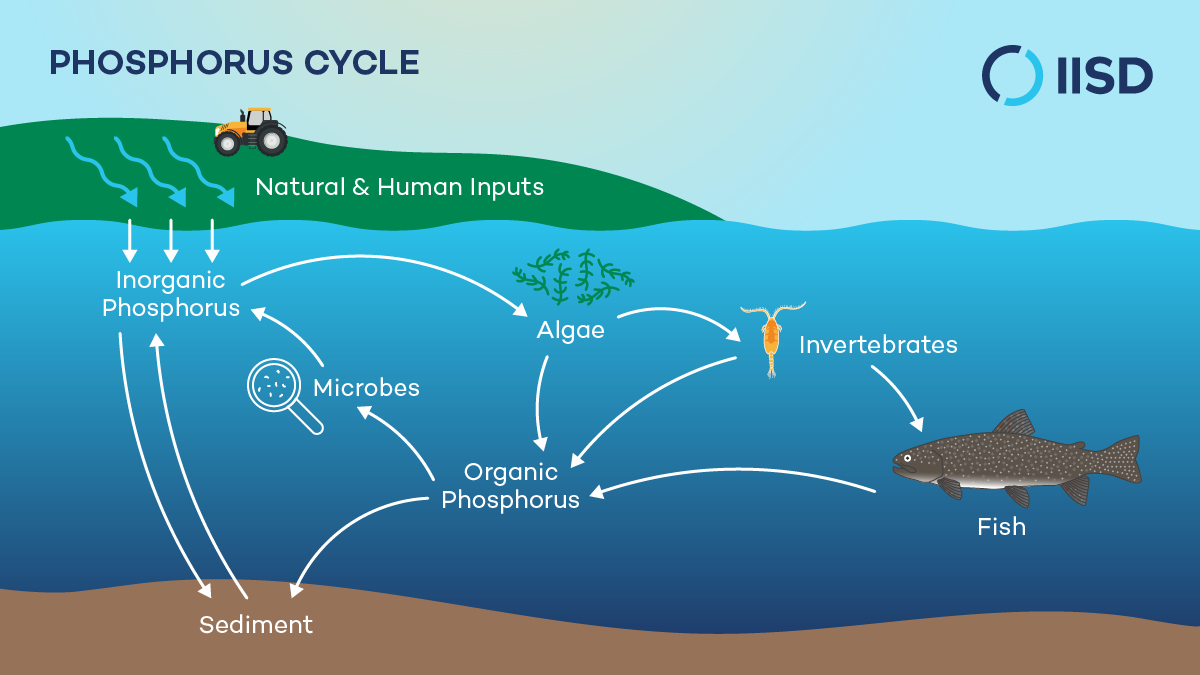

One lingering consequence of decades of farming, however, is that phosphorus is prevalent in the sediment lake beds of many Michigan waterways. Phosphorus is a naturally occurring nutrient that is essential for plant growth, but can cause eutrophication — when dissolved oxygen levels drop and suffocate fish.

“It's just a fact of life here, and the phosphorus from years of fertilization in these ponds were incredibly high,” Steinman said.

“So just to give a frame of reference, a natural lake around here that's not been impaired should be somewhere between 20 and 30 micrograms per liter, or parts per billion of total phosphorus. That's the normal goal you would shoot for.”

A high level of phosphorus in water is generally considered to be above 0.1 milligrams per liter (mg/L), which can significantly stimulate plant growth and lead to issues like algal blooms; for lakes and ponds, levels above 0.05 mg/L are often considered high and problematic for water quality, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Some of these repaired lakes, like Spring Lake, before we added the alum, was up around 100 parts per billion, so three to four times what you'd want. Lake Macatawa is 150 micrograms per liter, so we're constantly trying to work on that lake. Lake Michigan is one to two micrograms per liter, thanks to the quagga muscles that are filtering everything out of the water column,” Steinman said.

Steinman explained that the two primary methods of remediation are dredging sediment and applying alum (aluminum sulfate), which prevents the phosphorus in the sediment from being released into the water — both can be costly.

As the area surrounding Crockery Lake — now known as Chester Township — developed, parcels along the waterfront began cropping up and now exceed more than 100 homes and cottages.

What’s the problem in Crockery Lake?

The total phosphorus present in Crockery Lake ranged from 0.137-0.311 mg/L; the highest concentration was 0.860 mg/L. That’s according to Jennifer L. Jermalowicz-Jones, a Spring-Lake-based limnologist, or freshwater scientist.

In a proposal submitted to the Crockery Lake Association — a nongovernmental entity that works to preserve and improve lakes — Jones said she took water samples in May, July and September this year and submitted a remediation plan based around those results.

The association posted a copy of Jones’ plan on its website in October, saying that despite years of using traditional remediation methods, “our findings revealed that the complexity of the situation is more involved than what we, the residents, could manage,” according to the association’s website.

They also said they didn't want to seek chemical-based solutions to remediate the lake.

That’s when the association said it “connected” with Jones, who has her own restoration and lake management firm, Restorative Lake Services.

“After careful consideration, the CLA Board decided to contract her services to assess our lake and recommend a remediation plan that takes cost into consideration,” the association posted in October.

It’s unclear when Jones and the association started discussions, but the CLA hired Jones and her firm as early as September 2022 to perform testing for $6,500, according to CLA board minutes; she has continued to perform testing and various other services for the CLA since.

Political connections

As Jones began working for the CLA on Crockery Lake, an upstart political action committee called Ottawa Impact had just successfully challenged nine Republican incumbents on the Ottawa County Board of Commissioners.

The far-right fundamentalist group was formed by Joe Moss and Sylvia Rhodea in 2021 after they took issue with pre-K-6 school mask mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moss launched the group under the premise of “defending parental rights” and to “thwart tyranny” within the state and federal government.

Among the incoming OI commissioners in 2022 was Allison Miedema, who represents District 11, which includes Chester Township and Crockery Lake, and is returning next year after securing re-election in 2024.

Miedema said at the board’s Dec. 10 meeting that she had been working on bringing the Crockery Lake project about since before she was a commissioner.

“This is … something that I've been a very small part of for the last two and a half years,” Miedema said at the Dec. 10 board meeting. “I was brought up to date on it before I even took office in ’22 so it's not a quick thing that has come before us. It just happens to be that this is the time we're ready to present for the board's consideration.”

Jones has been connected to Ottawa Impact since at least early 2024, launching an unsuccessful bid this year for a seat on the Spring Lake Board of Trustees.

As part of her campaign, Jones published a website called SaveSpringLake.org, which was sponsored by the political action committee The Voice of Spring Lake. Among the committee members listed on Jones’ Save Spring Lake Committee is Moss, who was re-elected in November, and fellow OI-backed county commission candidate Jason Koert, who lost in the August primary.

A murky process

Despite Miedema claiming to have worked on the Crockery Lake project over many months, the Jones proposal didn’t come before the county publicly until a Nov. 8 finance and administration committee — sort of.

The proposal was not on the agenda for the committee to discuss that day, however, two members of the public — both CLA board members — spoke during public comment thanking the commissioners for helping with the lake’s remediation.

“I wanted to take this opportunity to personally thank the commissioners of Ottawa County for supporting lake remediation for Chester Township and for Crockery Lake,” said Paula Humphrey, who lives on the lake.

Humphrey noted that the funds would come from the Monsanto settlement money. In 2020, the U.S. agrochemical company paid over $10 billion to settle lawsuits involving the herbicide Roundup, which many litigants claimed caused cancer.

Ottawa County received $6.7 million from the settlement monies, which are to be used in water remediation projects.

Public discussion on the Jones proposal began in earnest at the finance committee’s next meeting on Dec. 3, however, the packet provided to the public only included a contract between Chester Township and the county — not Jones’ plan on which the contract was based.

The contract between the township and the county also drew concerns from Joe Bush, the county’s water resources commissioner, and attorney Stacy Hissong, general counsel for the Michigan Association of County Drain Commissioners.

Hissong asked commissioners at the Dec. 3 committee meeting who would be the owner of the contract — the county or the township — because it was not immediately clear in the existing language.

She also pointed to the lack of having the Jones plan accompanying the contract.

“It says the county board of commissioners has authorized the Crockery Lake restoration project to be designed and implemented by the company, and that's known as the contract as the project,” Hissong said. “And so … I'm not aware of an authorization of that contract between the county and Lake Restorative Services, and it's not attached as the document that the township is administering. So I just had some questions about that.

“I'm not sure what review of the contract has taken place between the county and Lake Restorative Services,” she said.

Hissong also said the contract lacked language addressing what happens if RLS is unable to secure the proper environmental permits.

“What if there's an unusual circumstance that a permit is not given, and so there can't be that type of work? This agreement doesn't provide for those funds being put back,” she said. “It doesn't have a timeframe.”

She also said she was “taken aback” by language in the contract between the municipalities that indemnified the township, a legal term where one party (the county) promises to compensate another party (the township) for losses, damages or liabilities.

Despite the issues raised at the Dec. 3 meeting, Jones said the Crockery Lake project as proposed could be used “as a tool for building a bigger framework for all of our county lakes.”

“We need a protocol or prescription to follow, and that's exactly what we hope to establish,” she said.

That set off alarm bells for some members of the public, who criticized the county for not putting the project through an official public bid process and not having Jones’ proposal reviewed by other science experts.

Seems quite self-serving,” Port Sheldon resident Dan Zimmer said during public comment. “A no-bid contract, an agreement arranged by Crockery Lake and a service provider, and it gets full buy-in by the board? Something is off.”

“You want the county to fully fund the restoration of a lake where shoreline property owners have already refused to take advantage of the self-help measures available to them — they could form a lake board — but they refuse to do that, and you're doing this while all the other lake communities in Ottawa County are left to fend for themselves,” said Ken Willison, of Spring Lake. “And you've made this very controversial recommendation without going through any sort of collaborative process first.”

Board majority moves forward

Despite the numerous questions and concerns raised at the Dec. 3 committee meeting, the OI members who hold majorities on all of the county’s committees, voted to advance the contract to the full board.

Interim County Administrator Ben Wetmore assured commissioners that the “minor” issues could be reworked and resolved prior to the commission’s Dec. 10 meeting.

He again assured commissioners at the Dec. 10 meeting that the project was “the product of months of discussions and negotiations, and the township has been very involved in a lot of meetings with the county.”

“Sending the contract back or undoing it at this stage would be really undoing a lot of legwork that has gone into this and a lot of negotiation to get everyone focused on this and there's a lot of legwork behind this that went into it by Chester Township and (Supervisor) Troy Goodno and the township’s council as well,” Wetmore said.

Minority members on the board during the Dec. 10 meeting, however, expressed frustration over what they described as a problematic process that felt rushed.

“There are many members of this board who have not been part of this process, and this is the exact moment where we are being brought into this process,” said Commissioner Doug Zylstra, one of two Democrats on the current board.

“So you may say it's been a long process, but until today, we've not been a part of that. So while I do appreciate your work on this, you know, there's a lot of folks here not on (the) finance (committee), we're not part of the discussion inside finance and outside of finance, and this is our first attempt to look at it,” he said.

Miedema said there was nothing untoward about the process and said that, “if a township is not able to perform the work on their own, for a variety of situations that is contingent on them reaching out to a county asking if they would partner.”

“For me, that would be a reason to consider why we're going with the contract allowing the township to take the responsibility, because it's not something that they're able to do on their own, and so it's asking for another governmental entity to come alongside of them, to assist,” Miedema said.

No representatives from Chester Township have spoken publicly about the Jones proposal at the Nov. 8 or Dec. 3 finance committee meetings, nor the Dec. 10 full board meeting. No formal correspondence from the township has been publicly provided documenting when and how the township may have asked for the county’s assistance.

Miedema said the township “has done their homework over the last several years, and Dr. Jones was who they chose after hours and hours of time researching who they wanted to go with.”

Commissioner Jacob Bonnema, who campaigned with OI in 2022, but publicly split from the group shortly after taking office in 2023, said the county shouldn’t just take a township’s word for it before doling out half a million dollars on a single project.

“Now, instead of us doing our own due diligence as a county before we hand out money, we're allowing another organization to do the diligence for us?” Bonnema said. “I guess the problem I have with that is, repeatedly during this conversation, it's been brought up that the (lake) association wanted to choose a natural method that didn't involve chemicals, so my understanding is that that necessarily limits the amount of practitioners that are going to be available to do this.

“We're tacitly approving their choice based off of not necessarily the compendium of science about all lake restoration methods, but just naturally originated ones,” Bonnema said. “That's just another wrinkle that I don't think necessarily fits with how our operating policies are as a county.”

Bonnema, who works in the insurance field, said the indemnification clause in the contract is problematic for the county.

“I see all the liability on us, and I don't see any proof of concept,” he said. “I would like to see this go back to council and potentially be opened up to a bidding process. I don't know why we've completely stepped over that, because that is a normal good business practice of every county … is to put things out for bid.”

He said the optics on the process don't embody transparency and appropriateness.

“This feels very rushed at the very end,” he said. “I know you're talking about how you've been aware of this since before you were elected, Commissioner Miedema, but why we're choosing a lake in your district in the last minute of this term? I don't think that's very clear.”

What happens next

The contract approved Dec. 10 is already facing one legal challenge after Grand Rapids-based attorney Sarah Riley-Howard filed for a temporary restraining order Dec. 16 that, if granted, would prevent the funds from being dispensed from the county to Chester Township.

Howard, who is representing Zimmer in the filing, alleges that a quorum of the commission “met secretly and out of public view either collectively and/or round-robin-style; sent representatives to meet and negotiate with Chester Township officials on behalf of the county without transparency to the entire commission; and purported to agree to commit county funds for the Crockery Lake project, which eventually became the subject of the contract.”

She said the vote at the Dec. 10 meeting was a fait accompli, or predetermined by the OI-affiliated majority commissioners before the meeting began.

Support Our Work

Ottawa News Network is a nonprofit news service dedicated to providing the residents of Ottawa County with trustworthy, community-driven news. ONN treats journalism as a public good — something that enriches lives and empowers Ottawa County’s 300,000-plus residents to stay engaged, make informed decisions, and strengthen local democracy. Please consider giving today.

Howard posed two legal challenges to the board’s approval of the contract, claiming commissioners violated Michigan’s Open Meetings Act and because the board does not have the legal authority to conduct a lake-improvement contract.

“A county board of commissioners cannot evade its jurisdictional limitations by funneling the entirety of the funds for a lake-improvement project through a township,” Howard wrote, noting that state law dictates that a county board of commissioners may only provide up to 25 percent of the cost of a lake-improvement project on any public inland lake and that a lake board is required and that a special assessment district be completed to help fund the project.

Crockery Lake has not formed a lake board as of publication.

— Contact Sarah Leach at sleach@ottawanewsnetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @ONNLeach.