Recently, I discovered a YouTube video showing a zebra stallion on a river bank holding in its mouth the hoof of a foal and suspending it upside down so that its head was submerged in the water. The stallion was stomping on its head to drown it. When the foal broke free, the stallion chased it, kicking and stomping it, hindered only by the mother trying to protect it.

(Check out “Zebra tries to kill foal” on YouTube if interested.)

A comment explained the stallion was protecting its genetics. Apparently, this foal, born to one of his mares, was not his offspring.

Other animals do the same — lions and grizzly bears in particular. I had come to terms somewhat with this behavior from aggressive carnivores, but it was more shocking to see it from a handsome, benign-looking zebra.

When I teach calculus to engineering students, I explain that the process of using mathematics and scientific principles to understand and predict natural-world phenomena is called modeling. The fewer and more universal the principles, the better.

For example, before Copernicus, the apparent motion of the planets was explained via cycles and epicycles. These are the motions of The Scrambler at an amusement park — seats spin around a small circle, and these in turn spin around larger circles. Since we observe planets seemingly going backward and forwards in the night sky, and since we supposed the Earth to be sitting motionless in the center of the universe, these small circles attached to bigger circles was the best way to explain what we saw.

Then along came the giants of modern science including Newton, Kepler, Galileo, and Copernicus. By the end of this period of rich discovery and mathematics, we had a new model for the heavens. The planetary movement we see is due to the planets — including the Earth — revolving around the sun at different speeds. Thus, from our perspective, some seem to be going backward at various times.

This explanation — this model — was far simpler than the one it replaced. Furthermore, it explained everything using only an understanding of the force due to gravity. One simple idea explained everything — and explained it more accurately than the previous model.

It has parsimony and beauty. It sits well. As Occam (Occam’s Razor) advanced, the simplest explanation is the most likely to be true. That is a guiding principle of science.

Indeed, is this not a guiding principle for anyone wanting to find the truth? For detectives, the usual suspect is often guilty.

Now, back to the zebra — and us humans.

I grew up learning an explanation for human behavior from the Heidelberg Catechism. It asserts that humans were created good, but the disobedience of Adam and Eve brought death, and all humans became wicked, corrupt and prone to hate each other (Original Sin). But those who believe the Christian Gospel live a New Life free from the bondage of sin and bringing forth fruits of righteousness.

This model offers some challenges. Is there a clear difference in behavior among those with the New Life? Also, how does this model explain the death and pain found among other animals? C.S. Lewis (“The Problem of Pain”) suggested that perhaps the same Evil Being who tempted humans to fall into sin had (before humans came on the scene) already corrupted the animals.

That, of course, is extra-biblical, but give Lewis credit for wrestling with it. Given the model he was trying to defend, it’s one solution.

But take my point: The model of human behavior offered by orthodox Christianity leaves much to be explained and gets rather messy and complicated in its attempt.

Another model: Naturalism. As can be shown mathematically, a person who steps randomly to the left or right will stay centered about the original point. But if there is a wall hindering movement in one direction, the person’s random steps will eventually take them far in the other direction.

Sentinel Leach is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Similarly, the model built on naturalism predicts that life, begun at the wall of simplest-possible-living organisms, will — via randomness built on mutations — eventually advance to increasingly complex lifeforms. That’s in fact what we find in nature.

The randomly mutated genes that outcompete their colleagues continue on — causing animals to behave as we observe in zebras, lions, and — yes — humans. Indeed, watch the squirrels around town compete and fight over food, mates, and territory. Then watch the evening news.

Does this prove naturalism true? Nope — but it’s worth pondering.

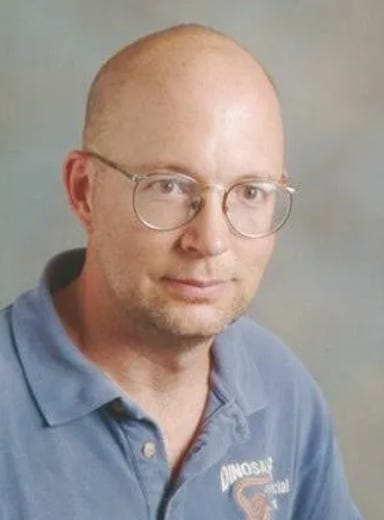

— Community Columnist Tim Pennings is a resident of Holland and can be contacted at timothy.pennings@gmail.com. Previous columns can be found at timothypennings.blogspot.com.